Chapter One

Reading Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo Through the Myth of Io and Argos

Mark W. Padilla

Critics and viewers have long recognized the presence of ancient Greek and Roman myths in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, including the stories of Orpheus and Eurydice (Brown; Poznar), Pygmalion (James 38–57), and even Helen of Troy (Mogg 149). Following the comparative approach that I have applied in previous analyses of Hitchcock’s films (in Classical Myth in Four Films of Alfred Hitchcock and Classical Myth in Alfred Hitchcock’s Wrong Man and Grace Kelly Films), in this present essay I focus on an additional archetypal story that underlies Vertigo, namely the story of Io and Argos. I first summarize the myth and discuss some of its transformations in art and classical literature. I then outline the broader themes that the film shares with the Io-Argos myth and explore parallels between characters in Vertigo and figures in the tale. In a final section, I consider analogues evident in the use of color and costume. All these elements are new in Hitchcock’s Vertigo: the source novel for the film, Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac’s D’entre les mortes (1954) and early screenplays are generally steeped in myth, but not in the Io-Argos story.

Summary of the Myth of Io and Argos

The story of Io and Argos is most famously recounted in Metamorphoses, an epic-style poem that the Roman poet Ovid composed in Latin in 8 CE. (For an extensive overview of cinematic uses of Ovid, see Winkler.) The same work also includes the stories of Orpheus and Pygmalion, and was a source for countless mythic references in literature and fine art, although there is no evidence that Hitchcock relied on Metamorphoses specifically for inspiration. The story of Io-Argos is also treated by earlier Greek authors and artists. The archetypal aspect of the story is thus best viewed as a composite of multiple sources. Though Ovid’s version emerges as the key telling, I refer to the characters of the story by their typically transliterated Greek names. The exception to this practice is the use of Latin names whenever Ovid’s story is invoked; there, Argos is spelled Argus, and Zeus, Hera, and Hermes (the featured Olympian gods) are referred to, respectively, as Jupiter, Juno, and Mercury.

Ovid begins his account of Io-Argus in Book 1, lines 583–688, and completes it after the interlude of another story, at ll. 713–750. The setting is the Argolid, near the city of Argos, in a rural location that includes the river Innachus, personified as a god of the same name. Innachus’s daughter is the naiad Io (naiads typically live in water, nymphs in woods). Just as she emerged from a swim in her father’s stream, Jupiter “had observed” her (l. 588; translations of the Greek and Roman passages throughout are my own), and he is immediately moved to have sexual relations with the fair maiden. This chief Olympian god announces himself to Io and invites her to meet him in the nearby woods for the tryst. After the unwilling Io runs into the woods to try and hide, Jupiter finds and rapes her (l. 600). However, he first covers their location with a manufactured cloud, an attempt to shield the event from his jealous wife Juno. Nevertheless, Juno has already noticed her husband’s absence: she “looked down” (l. 601) at the Argolid and notices the obscuring cloud. Juno flies down into it, but just before she discovers them together, the perceptive Jupiter makes a quick decision to “transform” Io into “a shining [white] heifer, a beautiful cow” (ll. 611–612).

The suspicious Juno adds the cow to her flocks, and then places a monstrous hundred-eyed shepherd named Argus in her service to guard over the animal. When Io traces letters in the dirt to convey her name and her fate to her grieving father, Argus moves Io to a higher pasture, and perches himself on a knoll with a wide vista (ll. 666–667). Moved by Io’s suffering, Jupiter sends Mercury to slay Argus. Mercury dresses as a shepherd and puts Argus to sleep with his wand and by playing his panpipes and telling him a story (that of Syrinx, the victim of Pan). Argus soon closes all of his eyes, and Mercury beheads him. Juno’s sacred bird is the peacock, and as the body and head roll from the knoll, she transfers his eyes to the plumage of the bird’s train for adornment.

Juno next impels a “horrific Fury” to force Io into a torturous circuit “through the whole world” (l. 727). After wandering in southeastern Europe and western Asia, a journey giving name to the Ionian Sea and the Bosphorus (“Ox-ford”) Straits, Io arrives in Egypt. Juno accedes to her husband’s wish to end Io’s suffering, which Jupiter does when he “touches” her body. When Io regains her naiad state, she also discovers she is pregnant and soon gives birth to Epaphus (“He-of-the-Touch”). Finally, the Egyptians accept her as their goddess Isis – a motif that perhaps betrays an original Near Eastern influence. Isis wore the headdress of the primeval Hathor, which included the bovine elements of horns; apparently, too, “a celestial cow conducted the dead pharaoh to a heavenly throne” (Davison 55). The descendants of Io later return to Greece, and her long lineage of heroes and heroines include such important figures as Perseus and Heracles.

The Io-Argos Myth in Art and Literature

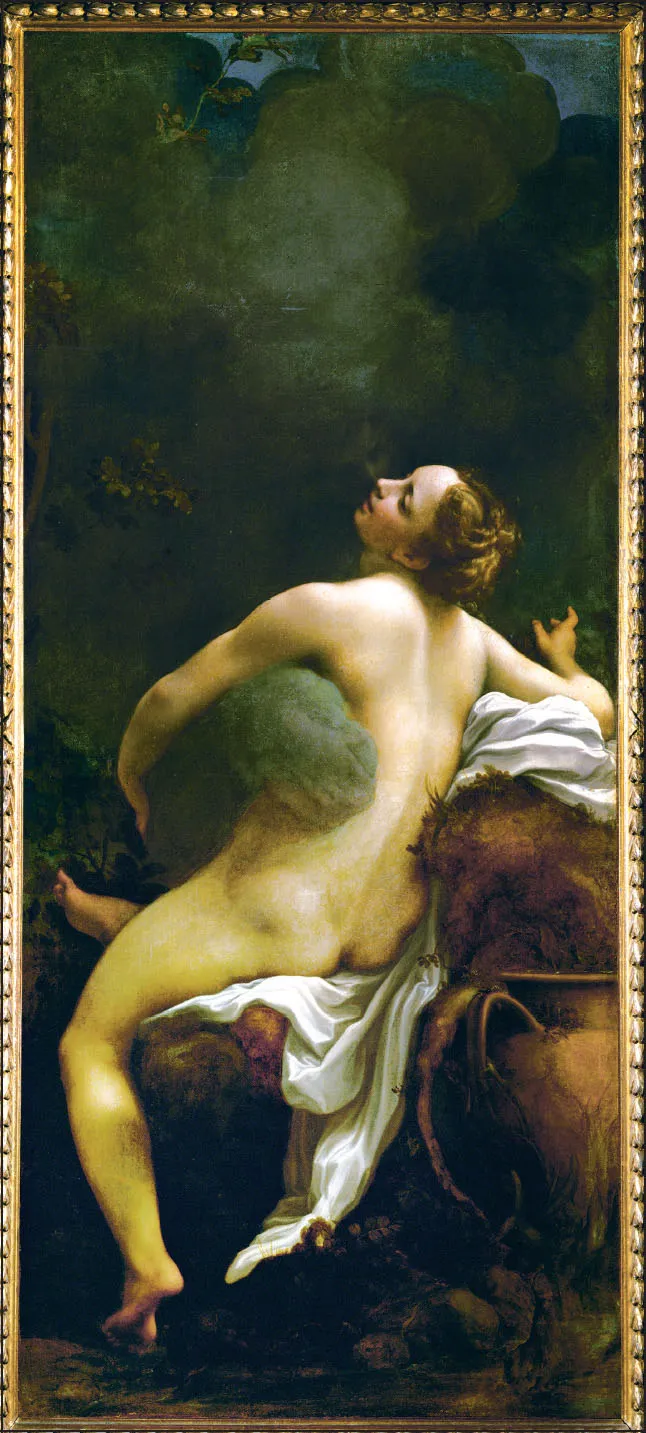

The Io-Argos myth may not be as well known today as it was in antiquity, in the Renaissance, and in later periods, but it would be incorrect to view the story as a minor one. The story adorned Greek vases, and in the Roman world the story was depicted on dozens of walls in Pompeii (see Icard-Gianolio).1 Indeed, the tale’s variety of motifs offered its adapters a range of narrative emphases, with four core elements: eroticism and jealousy; the colorful monstrosity of a multi-eyed monster guarding a maiden-as-cow, a monster then slaughtered by Hermes; the pitiful wandering; and the resurrection and birth. The story remained popular in Western fine art. The most famous painting of the story is found in Correggio’s masterpiece, Jupiter and Io (fig. 1).2 Here Zeus has taken the form of an opaque cloud and ravishes the foregrounded and nude Io. The Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in the Arts, 1300–1990s (Reid 594–599) lists 153 entries for the Io myth, including treatments by Fragonard, Kauffmann, Lorrain, Poussin, Rembrandt, Rubens, and Velázquez. Such fine art treatments offered a means by which other kinds of artists, such as writers and film directors, could remain conversant in classical myth. We should recall that Hitchcock was a regular patron of art galleries.

Figure 1. Antonio da Correggio (1489-1534), Jupiter and Io (c. 1520–40). Oil on canvas. Kunsthisorisches Museum, Vienna.

Ovid’s account of the Io-Argus story depends upon earlier Greek iterations, antecedents that thematically expand the register of Ovid’s sensationalist emphasis. The early epic poem in which Hesiod treated the story unfortunately survives only in a few in fragments (see Ganz 1:198–202), but his Io, rather than being the daughter of the river Innachus, serves as a temple priestess of Hera near the city of Argos, an element that explains why Ovid’s Juno happens to be concerned with the Argolid. Hera’s association with the wealth of cattle reinforces her elite status, and Homer provides her the epithet “cow-eyed”. Hesiod, furthermore, attaches to Argos the epithet “panoptes” (“all-seeing”), and presents him as the shepherd of Hera’s sanctuary flocks. The origin of this monster figure perhaps extends back to an indigenous pre-Greek figure of regional cult, for his second epithet is “earth born”. Early Greek poems, finally, endow Argos with a set of heroic associations outside of the Io tale. For example, Argos hunts and slays a wild bull, and then clothes himself in its hide, the spots prefiguring his monstrous eyes.

In analyses of the Io-Argos story, scholars have emphasized themes of ritualism. Walter Burkert develops a paradigm of kingship succession (162–168). The bull sacrifice motif, found in Hermes’s murder of the bull-hide-covered Argos, signifies an inter-regnum moment, or event of “dissolution” in the story, namely a period in which the cows in the bull’s herd are viewed as leaderless and begin to wander aimlessly as if “mad”. Thus, a new leader is needed and awaited, such as the newly-crowned Zeus. The ritual paradigm, furthermore, is akin to the New Year’s celebration (releasing one year and receiving another), of which the festival of Hera at her Argos sanctuary served as a variation. In turn, Ken Dowden locates this early figure of Io in the nexus of girls’ initiation rites, organized in a tripartite progression of youth-to-adult identity formation (116–145). Io’s loss of her virginity symbolizes a separation from girlhood. Her transformation into a heifer and wandering are key elements in the process of liminal transition. Io achieves womanhood when she becomes a mother and a goddess.

Greek tragedy in the fifth century BCE includes the wandering Io in Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound. At the start of the play, Zeus sends his henchman to punish Prometheus – the Titan who stole Zeus’ fire and gave it to humans – by pinioning him to a crag on the Caucasus mountains, a range that connects the Black and Caspian Seas. The horned Io enters at line 561, impelled by the ghostly specter of Argos. For the next 326 lines, the two victims of Zeus empathize with each other’s suffering. For example, Io shares some of her terrifying experiences as an “ill-wandering maiden” (l. 585), and Prometheus prophesizes that Io will wander through many lands. In Aeschylus’s Suppliant Women, the action focuses on Io’s descendants and frequently references her. Here, the fifty daughters of Danaus, or Danaïds, are told to marry their fifty cousins, sons of Danaus’s brother Aegyptus, and the action is set in Argos, where the Danaïds have sailed to elude their suitors. The historian Jean Davison suggests the Io story was used by Aeschylus as part of a reflection on Greek colonization: seafaring wanderers allegorized in the Io myth represent Greek interactions with foreign peoples that tested and ultimately confirmed the presumed superiority of their Hellenistic values.

Themes of the Io-Argos Myth in Ovid, Hesiod, and Aeschylus Reflected in Vertigo

Vertigo shares numerous themes with Ovid, early epics, and Athenian tragedy. For example, Ovid’s presentation of motifs of metamorphosis anticipate and parallel much of what we see in Hitchcock’s film, and Vertigo shares with Ovid themes of deception and infidelity, identity transformation, madness, male sexual obsession and control, storytelling, violence, voyeurism and spectacle, and wandering. Hesiod and other Greek poets, in turn, work with the ritualistic patterns of doubles that cancel out one another. For example, the shepherd Argos kills and dresses as a bull, and Zeus sends Hermes as a shepherd to kill the shepherd Argos. Zeus’ action establishes himself as the new king of Argos, a violent rite of dissolution and substitution that politically extends his recent overthrow of the Titan Kronos (Burkert 168). Vertigo, in turn, is replete with the symbolism of self-cancelling doubles and the related motifs of dissolution and substitution. For example, the detective John “Scottie” Ferguson (James Stewart) nearly falls from the roof, but a policeman dies instead. Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) is Scottie’s college friend, and both are ambitious: Elster aims for still more “power and freedom”, while Scottie once sought to become a police chief, and then covets the rich Elster’s wife. However, Elster implements a plan to become independent and free of his wife, while Scottie, who suffers from acrophobia, experiences a nervous breakdown. Judy Barton (Kim Novak) disguises herself as Madeleine Elster, and the real Madeleine is then killed. Marjorie “Midge” Wood (Barbara Bel Geddes) paints her face into the Carlotta painting, in an attempt to erase the erotic hold Madeleine has over him, while Scottie thinks the ghost of Carlotta has taken over Madeleine. At the end of the film, Judy erases herself as such to re-create Madeleine, but Scottie realizes the truth and cannot accept her.3 The stories of “the mad Carlotta” and the wandering of Madeleine and Scottie are also examples of the link between doubling and dissolution. Midge once enjoyed a romantic relationship with Scottie, and now waits for its return. Judy develops a relationship with Elster but is set aside and she is soon courted by Scottie, only to have Scottie dissolve her identity as Judy.

The early Greek interest in Io relates to identity formation ritualism (see Dowden), and the multiple characters Novak plays evoke this motif. Judy left her home in Kansas when her father died. Elster then somehow discovered her and transformed her into the glamorous Madeleine. Elster, however, abandons her, and Judy enters into a relationship with Scottie. In an ironic inversion of the three-stage child-to-adult pattern, the linear process by which a girl becomes a woman, at the end Judy shifts back into her transition stage, and the loss of her life symbolizes the identity chaos of that liminal state. While Io rises up as a goddess and mother from her bovine state, Judy falls down from the tower to her death and may be said to rejoin Mother Earth, symbol of her origins, in an ultimately cyclical rather than linear progression that denies her Io’s transformational progression.

Finally, as mentioned above, Aeschylus’s two plays feature the figure of Io in the context of a consideration of Hellenic-versus-foreign values, an element that Vertigo similarly incorporates in its references to Spanish California (especially in the visits to the two missions). The Spanish established missions that displaced natives; Americans from the east then came and wrested California from the Spanish. Thus the “double and dissolution” theme is extended into ideas of epochal progression, visually expressed in the state park’s exhibition of a cross section of an ancient tree, a naturalized image of civilization’s ongoing record of political and militaristic imperialisms that characterize human history.

Character Parallels

The next four sections discuss the salience of the Io-Argos myth in Vertigo by examining broad rubrics of character parallels, noting ways in which Midge projects the jealous Hera, Elster evokes the powerful Zeus, Judy embodies elements of both Io (in her role as Madeleine possessed by her great-grandmother Carlotta) and Hermes (as Elster’s assistant), and Scottie is analogous to Argos.

Midge as Hera

In the broader pattern of the Io-Argos story, Hera disappears from the action when Io initiates her travels. Midge offers a parallel for Hera in this context, because in the last third of the film, Midge too disappears from the f...