![]()

1

INTERNATIONAL DOMINATION BY THE U.S. FILM INDUSTRY

In the one hundred years since World War I, the U.S. film industry has grown into the world’s largest. It often draws more spectators to its films in foreign markets than films produced by the national film industries in those countries. In the second half of the twentieth century, various countries took measures to protect their national film industries, but they did so without coordination with other countries. Before the spread of television, the cinema had no rival as a mass entertainment medium, and many national cinemas produced waves of internationally renowned films during the 1950s and 1960s.

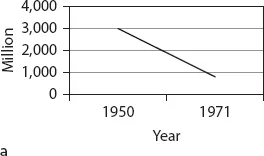

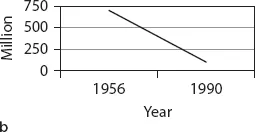

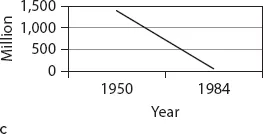

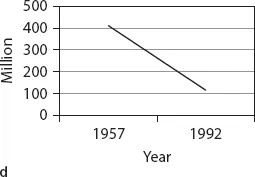

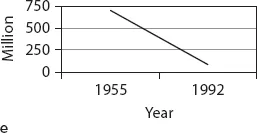

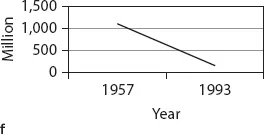

During the 1950s, theatrical attendance reached unprecedented heights in most countries, then fell spectacularly, with Hollywood taking the first and fastest plunge. Hollywood lost almost three-fourths of its audience in theaters between 1950 and 1970; some of the largest European film industries saw audiences decline by almost 90 percent (see figures 1.1a–1.1f).

FIGURE 1.1a Cinema attendance, from post–World War II high to low in the United States (total loss was 73%)

FIGURE 1.1b Cinema attendance, from post–World War II high to low in Germany (total loss was 84%)

FIGURE 1.1c Cinema attendance, from post–World War II high to low in the United Kingdom (total loss was 96%)

FIGURE 1.1d Cinema attendance, from post–World War II high to low in France (total loss was 72%)

FIGURE 1.1e Cinema attendance, from post–World War II high to low in Italy (total loss was 88%)

FIGURE 1.1f Cinema attendance, from post–World War II high to low in Japan (total loss was 86%)

Historians have identified multiple factors behind this worldwide decline, including the rise of television, the expansion of alternative leisure activities, and the introduction of VHS and DVD.1 Nonetheless, theatrical exhibition remains the crucial first window for the cinema industry, even if downstream windows now supply the bulk of revenues.2 After hitting bottom in the early 1970s, Hollywood recovered later in the decade and pressed its advantage internationally, leading to its massive domination of most national markets. Following the conclusion of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) negotiations in 1993, many countries, led by France, managed to arrest that dominance and demonstrate that submission to U.S. hegemony was not inevitable. Even as parochial discussion in the United States prefers to stigmatize government involvement, France has shown that in the increasingly globalized and digital world, national industries can survive if—and probably only if—the state intervenes judiciously to support both commercial success and artistic ambition. In many ways, globalization has been driven by an ideology of free trade, dismantling barriers to trade erected by individual countries. In earlier years, countries might object to pressures to open their markets, but free trade agreements in the most recent era of globalization locked countries into commitments to lower trade restrictions. Consequently, resistance has required building counterhegemonic alliances, for globalization seeks to weaken the power of states, especially alone, to control the more harmful consequences of free trade fundamentalism.

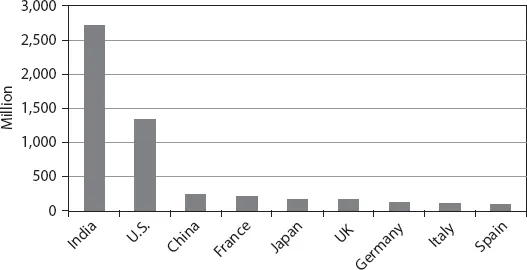

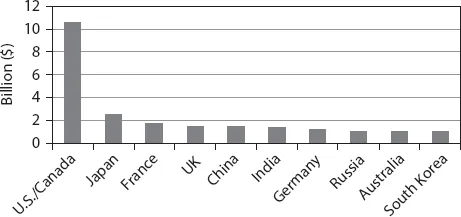

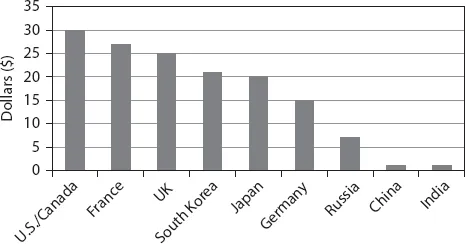

Before we look more closely at forms and sites of resistance to Hollywood hegemony, contextualizing the contours of the film industry internationally provides a needed perspective. A small number of developed countries account for most of the production, attendance, revenue, and screens across the world. It is often claimed that India has the largest film industry in the world. In certain ways, that claim is accurate but also misleading. India does produce more films than any other country, and its films draw many more spectators in theaters than any other country, as figure 1.2 indicates. Indian cinema also dominates its domestic market, capturing over 90 percent of all theatrical attendance.3 However, in other significant ways, Indian cinema pales in relation to that of the United States. In absolute terms, Indian cinema earns less than 15 percent of U.S. domestic movie revenues, even with a population four times as large and twice as many spectators. The average Indian films costs about $500,000, compared to an average of $60 million in the United States. More detailed comparisons are difficult to make because of the absence of available figures for Indian cinema, but it is safe to say that promotion costs in India are a small fraction of what is spent on U.S. films. Once one begins to factor in the enormous size of India’s population, the figures reveal a popular but financially modest industry compared to other countries with much smaller populations. India has over 1.3 billion people and ten thousand movie screens; with less than a quarter of India’s population, the United States has almost forty thousand screens. France, with only 62 million people, has 5,500 screens, and annual theatrical revenue of the French film industry exceeds India’s box office. With population factored in, India’s per capita box office revenue ranks below that of all other major national film industries (see figures 1.3–1.4).

FIGURE 1.2 Theatrical attendance in selected countries, 2010

FIGURE 1.3 Domestic box office receipts in U.S. dollars, 2010

FIGURE 1.4 Per capita box office revenues in U.S. dollars, 2010

The comparison becomes even more dramatic beyond the borders of the two countries. Plausible anecdotal evidence suggests that Indian cinema is popular in other countries, but those countries are generally poor, with small markets and film industries. Despite the critical interest in Indian cinema in more developed countries, Indian cinema barely registers in the domestic box office of the developed world.4 Even in a country like Great Britain with a considerable population of people with Indian backgrounds, and where some observers find a sizeable audience for Indian films, the market share for such films is probably no more than 1 percent.5 Indian films do attract diasporic Indian spectators, but those films rarely compete with non-Indian films in the developed world. In addition, the Hindi-speaking cinema known throughout the world as Bollywood represents less than 20 percent of polyglot India’s annual production, so most Indian national production goes virtually unseen outside its borders by nondiasporic audiences.6

The People’s Republic of China is another special case. Also with a population of more than a billion people, annual theatrical attendance reaches 400–600 million, or one-fifth of India’s total. Figures are also elusive for the PRC’s cinema industry, but revenues appear to have exploded in recent years from $455 million (2007) to $3.5 billion (2013), leaping past India ($1.6 billion).7 While estimates of the number of theatrical screens in China vary wildly, some sources indicate that the number of “modern” screens rose from 6,256 (only slightly more than France) in 2010 to 18,195 in 2013, still less than half the number in the United States. It is difficult to ascertain the export numbers for Chinese cinema, and the brief emergence of Hong Kong cinema as a phenomenal industrial success, producing hundreds of films popular throughout Southeast Asia, complicates the story, to say nothing of the film festival embrace of Taiwanese cinema in recent years. That particular constellation of three Chinas has led scholars to speak of Chinese cinemas, since the films and filmmakers increasingly cross the political borders.8 And political considerations play a critical role in the PRC cinema, for the government strictly controls the number of non-Chinese (and Chinese) films permitted to be shown in theaters. Thus, China allows only a small number of foreign films into the country each year, primarily U.S. films.

In the context of this book, the Indian and Chinese cinemas each represent anomalies. Both of their cinema industries maintain large domestic market shares of the theatrical audience. Without (or with few) import restrictions, Indian cinema consistently draws over 90 percent of the annual attendance. With so few foreign films allowed to enter the country, China’s domestic market share also remains high, but that situation appears to be changing, as China has raised the number of films it imports, and since the domestic audience has been given the choice of watching more foreign films, the Chinese film industry’s domestic market share has begun to decline, dipping below 50 percent in 2012.9 Together, then, the two countries with the largest populations in the world produce a large number of films, seen by billions of spectators, with only modest box office revenues compared to the rest of the world. But the reach of their cinemas beyond their borders is limited to their regional neighbors or diasporic communities.

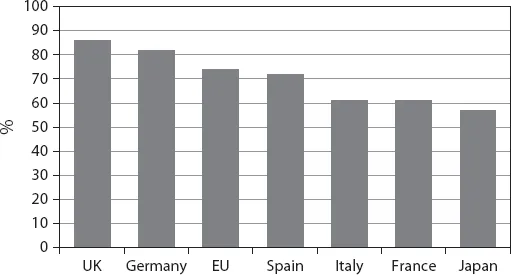

In most other countries, including all the wealthiest developed countries, the U.S. cinema draws a staggering percentage of domestic viewers, and domestic market share is arguably the best single measure of the health of a national film industry.10 Setting aside for the moment technical questions regarding the nationality of films, and excluding the special cases of India and China, U.S. films garner 70–80 percent of the world theatrical cinema box office.11 However, the market shares for domestic industries have improved in many countries over the past two decades, suggesting that cinema industries may still be viable in other countries and perhaps even more significantly, that the medium of cinema, as a theatrical phenomenon, has a future, defying the many prognostications of its death in recent years. But given the massive Hollywood presence on screens in so many countries, the nature of that future remains unclear.

In 1995, a famous Variety headline appeared to be true: “Earth to H’wood: You Win!”12 At the time, the Hollywood market share in the most developed countries, with the largest national film industries and the most remunerative foreign markets, stood at roughly 70 percent; the Variety article reported that Hollywood films took in 90 percent of world cumulative box office revenues of $8.34 billion (see figure 1.5).

FIGURE 1.5 Percentage of U.S. market shares, 1994

For many years, however, voices have expressed concern about this domination, often under the rubric of “cultural imperialism.” According to these critics, cultural products like movies have potentially negative effects on foreign audiences, for they spread ideological influence that both crowds out home-grown cultural expressions and imposes uniformity in the cultural sphere, which can thrive only through diversity.13 This critique has also spawned responses that question the implicit—and condescending—claim that foreign audiences are incapable of deciphering the ideological influence and developing their own creative works that are not mere reproductions of the hegemonic Yanqui culture.

These kinds of tensions and contradictions fuel reductive accounts describing some kind of deeply rooted French hostility to the United States, sometimes described as pathological.14 Cultural commentators in both countries pluck evidence from any number of domains, whether literature, the art world, or cinema. In 2007, a U.S. writer based in France wrote an article for Time with the Proustian title “In Search of Lost Time.”15 For the European edition, Time designed a cover with a photograph of Marcel Marceau, complete with beret, and splashed a new title across the cover, no doubt in search of French readers: “The Death of French Culture,” followed quickly by a book with the same title. The author, Donald Morrison, inventoried the alleged contemporary irrelevance of French culture. According to him, few people outside France read French books, museums showed little interest in French artists, and French cinema had produced no filmmakers of international renown since Truffaut and Godard in the 1960s. Though writing as a self-described Francophile (living in “a country I rather like”), Morrison examined the traditional arts and found no prominent contemporary French artists in any area, with the lone exception of architecture. Unsurprisingly, angry reactions poured forth in the French press.16

...