History

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. It was caused by a combination of drought, poor farming practices, and high winds, leading to widespread soil erosion and economic hardship for many farmers. The Dust Bowl had a significant impact on the environment and the economy of the affected regions.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Dust Bowl"

- eBook - ePub

Drought

An Interdisciplinary Perspective

- Ben Cook(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

SIX Case Studies The Dust Bowl and Sahel DroughtsA mong the many persistent droughts that occurred during the 20th century, two events are notable for their intensity, their impacts, and the interest they generated in the scientific community. The first is the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, a nearly decadal long drought that afflicted much of the central plains in North America. Combined with a major economic depression and poor land-use practices, this drought became one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history, resulting in historically high levels of land degradation, human migration, and dust storm activity. The second is a persistent drought that affected the Sahel region of West Africa from the late 1960s through the early 1990s. This multidecadal period of below-average rainfall ravaged ecosystems and subsistence farming communities in the region, inspiring new schools of thought and investigations into drought, desertification, and climate change. Here, we review these major droughts, discussing their causes and impacts (including the role of human activities) and some of the major lessons learned from studying these events.The Dust BowlThe term Dust Bowl was coined in 1935 by Robert E. Geiger after Black Sunday, a massive dust storm that blew across the Oklahoma Panhandle on April 14, 1935. Geiger, an Associated Press reporter, experienced the storm in Boise City, Oklahoma, and afterward would write, “Three little words achingly familiar on a Western farmer’s tongue rule life in the Dust Bowl of the continent—if it rains” (Worster, 2004). Originally, the term was used to refer to the specific area of the southern plains near the Oklahoma and Texas Panhandles that was the center of the most intense dust storm activity and wind erosion during the drought. Later its use would expand, and Dust Bowl - eBook - PDF

Earth's Fury

The Science of Natural Disasters

- Alexander Gates(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

It was blown all the way into New England, New York City, and even Washington, D.C., where legislators experienced just a hint of what almost one-third of the United States was suffering through. It was the result of this storm that an Associated Press reporter used the term Dust Bowl for the first time to describe this disaster in the Central Plains. Human costs associated with the Dust Bowl were enormous. Much of the United States was suffering through the effects of the stock market crash of 1929 and onset of the Great Depression, but the Central Plains was relatively insulated from this economic disaster. Farmers grew their own food and maintained a reasonably unchanged lifestyle. The Dust Bowl literally blew away their livelihood, and they could no longer make mortgage and tax payments on their farms. Many people were forced to abandon their homes and seek a new life somewhere else. The largest mass migration in American history resulted with more than 2.5 million people leaving the Central Plains states and set- tling elsewhere by 1940. About 15% of the people in Oklahoma left the state, many moving westward and settling in California. Other parts of the country were overwhelmed with the influx of Dust Bowl refugees, collectively called “Okies,” even though they were from several states. The Great Depression was in full swing by this time and these transient newcomers stressed local relief services and competed with local resi- dents for jobs, often willing to work for greatly reduced wages. N Dust Bowl States Area with most severe dust storm damage Other areas damaged by dust storms New Mexico Colorado Wyoming Montana North Dakota South Dakota Nebraska Kansas Oklahoma Texas Texas FIGURE 17.8 Map of the United States showing the Dust Bowl states and area damaged by dust storms. Droughts and Dust Storms 349 Government response to the disaster was slow. - eBook - PDF

- Matthew J. C. Cella(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- University Of Iowa Press(Publisher)

In this way, the Dust Bowl narratives of Olsen and Manfred present a form of social and historio-graphical critique; in addition, they refashion the promise of pastoralism to fit the contours of a fallen and ruined biocultural landscape. As tragicomic narratives, that is, these representative Dust Bowl pastorals begin the work of assessing the postfrontier Plains. The Dust Bowl as a Tragicomic Biocultural Event In many ways, the spectacle of the Dust Bowl merely images the same old story on the Plains, providing another example of the specific challenges that the bioregion throws up against Euroamerican paradigms of inhabitation. While perhaps more severe and prolonged than previous droughts experi-enced on the Plains after Euroamerican settlement, the Great Drought of the 1930s that created the Dust Bowl was just another manifestation of the bio-region’s relatively predictable cycle of wet and dry seasons. What makes the Dust Bowl such a significant event in the overall pattern of “bad land” events from the Euroamerican perspective is the scale of the crisis and the severity of its physical and spiritual consequences. The greatest human tragedy of the Dust Bowl was the massive depopulation of the Plains and the forced displacement of thousands of families. Paul Bonnifield notes how “in the main, the region’s economic life fits into the general trends of the national depression. Times were ‘hard’ everywhere” (105). In this sense the economic crisis of the Dust Bowl was merely a regional symptom of a national, and even global, phenomenon. The collusion of national trends and regional 138 patches of green and fields of dust experience produced a perfect storm of forces that challenged the values and principles at the core of the biocultural development of the Plains. - Char Miller(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

During the 1910s and 1920s, farmers had plowed many acres of land previously left fallow or devoted to pasture for cattle. In 1890, only 5,762 farms and ranches were located in areas that would be affected by the Dust Bowl in Kansas, Colorado, and Texas. By 1910, this number had nearly doubled to 11,422. Most farmers developed their land without attention to conservation practices like crop rotation and terracing and plowed to the very edges of their property in their eagerness to make a profit. Land that was already dry and sandy was no longer anchored by native grasses, making it particularly susceptible to wind erosion. This resulted in day after day of dirt storms, ranging from a simple haze of dirt in the air to rolling black storms that blotted out the Sun. During one particularly bad dust storm in 1935, geologists in Wichita, Kansas, estimated that 5 million tons of dust were suspended over the city. Breathing this fine dirt led to respiratory ailments, for example, dust pneumonia in humans, and caused the deaths of untold numbers of cattle and other livestock. Impact. The costs were enormous, in human, economic, and environmental terms. During the Dust Bowl, thousands left the Great Plains. The population of Dust Bowl counties, on average, fell 25 percent, with 50 percent or more leaving in particularly hard-hit areas, including Morton County, Kansas, and Baca County, Colorado. Those abandoning their farms most commonly made their way west to California, Oregon, and Washington. Those that remained endured a decade of hardships- eBook - ePub

Exploring Environmental Issues

An Integrated Approach

- David D. Kemp(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The image of the Great American Desert had paled, and the settlers farmed just as they had done east of the Mississippi or in the Mid-west, ploughing up the prairie to sow wheat or corn. By the 1880s and 1890s the moist spell had come to an end, and drought once again ravaged the land (Smith 1920), ruining many settlers and forcing them to abandon their farms. As many as half the settlers in Nebraska and Kansas left their farms at that time (Ludlum 1971), like the earlier inhabitants, seeking relief in migration, in this case back to the more humid east. Some of those who stayed experimented with dry farming, while others allowed the land to revert to its natural state, and used it as grazing for cattle, a use to which it was probably much more suited in the first place. The lessons of the drought had not been learned well, however. By the 1920s the rains seemed to have returned to stay and a new generation of farmers moved in. Lured by high wheat prices, they turned most of the Plains over to the plough, seemingly unaware of the previous drought or unconcerned about it. Crops were good as long as precipitation remained above normal, but by 1931 the good years were over and throughout the remainder of the decade the Plains were plagued by dust storms which carried away tens of millions of tonnes of topsoil. In combination with the rundown economic state of the country and the world at that time (a period commonly known as the Depression), these conditions created such disruption of the agricultural and social fabric of the region that the effects have reverberated down through the decades, and the Dustbowl remains the benchmark against which all subsequent droughts have been measured. The only possible response for many of the drought victims of the 1930s was migration, as it had been in the past - eBook - PDF

The Economics of Climate Change

Adaptations Past and Present

- Gary D. Libecap, Richard H. Steckel, Gary D. Libecap, Richard H. Steckel(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

82 John Landon-Lane, Hugh Rockoff, and Richard H. Steckel parts of New Mexico during 1930 to 1936. The dust storms are legendary, and the economic distress became an enduring part of the nation’s cultural landscape with the publication of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Somewhat surprisingly, given the role of the Dust Bowl in American cultural history, the Instrumental Palmer Drought Severity Index for Okla-homa and Texas shows that the drought of the 1930s, although severe, was far from extraordinary. By this measure the drought was much less severe than the drought that hit in the 1950s. Hansen and Libecap (2004) explain that the severity of the agricultural crisis in the 1930s was due in part to the prevalence of small farms that did not engage su ffi ciently in practices to limit wind erosion. The economic su ff ering, of course, was greatly aggravated by the low farm prices that prevailed during the Depression. Nevertheless, a closer look at this episode will shed some light on how weather- driven agricultural distress challenges local financial markets. Historians of western banking are clear that the distress that resulted from the Dust Bowl was felt much more intensely by the small state chartered banks and private banks that served rural parts of the a ff ected regions, rather than by the national banks that served urban areas. In particular, the rural banks lost money on livestock loans (Doti and Schweikart 1991, 144). Indeed, the national banks may have benefited to some degree from an Fig. 3.2 The rate of return to equity in national banks, Kansas and the national average, 1870–1910 Source: State level rates of return to bank equity compiled by Scott A. Redenius; see text. Droughts, Floods, and Financial Distress in the United States 83 3. This conjecture is suggested by Bernanke (1983). attempt by depositors to switch funds from risky rural banks to the larger and safer national banks. - eBook - ePub

Nature, Class, and New Deal Literature

The Country Poor in the Great Depression

- Stephen Fender(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Again, contrary to the popular story, the rush to California did not peak during the Depression. Rumors of new opportunities and a temperate climate, later reinforced by the glamour of the movies, had been attracting Southwesterners to the state since the second decade of the century. Between 1910 and 1930 more migrants arrived—albeit with more skills and savings than the Okies—than during the whole of the Depression. In the 1940s California war industries like shipbuilding and aircraft manufacture pulled in nearly twice the numbers of those supposedly blown off their farms in the Dust Bowl.That phrase “Dust Bowl” itself, though certainly based on horrific concrete events, came to stand in as misleading shorthand for the whole migrant experience. For people in Texas, Arkansas and Oklahoma the mid-30s drought and economic hardship were real enough, but the truly devastating dust storms were restricted mainly to the western half of Kansas, the southeastern corner of Colorado and the eastern border of New Mexico; they brushed past Texas and Oklahoma only at the panhandles where the two states meet, and missed Arkansas by four hundred miles.2 The process by which that dust, the most striking image of a widely perceived natural catastrophe, came to displace the social and economic causes of the Okie migration in the popular consciousness and memory, is the story of this chapter.What the historians do accept, though it remains much less prominent in the popular memory, is that the migrants were unprepared for the kind of agriculture they found in California. Farms in the Central Valley were huge, involved in specialized agribusiness before that term was coined. Instead of being settled after the Jeffersonian ideal of small family homesteads, California farms had evolved top-down from large estates that had originally been Mexican land grants. They were big and commercial, too, because of their need for water: away from the rivers running south and north down its center, most of the Central Valley was desert. This meant irrigation, and irrigation needed plenty of capital. The scale of the operation also tended toward specialization: at first in wheat, until that market collapsed in the Depression; then in fruit and vegetables, as the railroads developed efficient “reefers,” insulated box cars refrigerated by stacks of ice at both ends, to carry chilled produce across the continent to eastern markets. - eBook - ePub

- Sam White, Christian Pfister, Franz Mauelshagen, Sam White, Christian Pfister, Franz Mauelshagen(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

This has been particularly true in semiarid regions, because as Michael Glantz and colleagues have argued, “drought follows the plow”: that is, temporarily moist conditions permitting an expansion of arable land or pasture will sooner or later turn dry again. For instance, the American Dust Bowl of the 1930s was only one of many recurring droughts to hit the Great Plains in recent centuries. What made this drought a human disaster was the extension of wheat cultivation during the preceding decade, which probably aggravated drought conditions and erosion and left more farmers vulnerable to crop failure during the hard economic times of the Great Depression. 50 Other Dust Bowl events and agricultural failures in semiarid regions of Australia, Canada, the Soviet Union, and the African Sahel during the twentieth century followed a similar pattern. 51 In the case of the Sahel famines of the 1970s and 1980s, anthropogenic aerosol pollution may have aggravated regional drought conditions (see Chap. 26). Furthermore, parts of the world during the twentieth century remained vulnerable to ENSO fluctuations and their associated weather patterns, particularly in Latin America, the Pacific, and South-East Asia (see Chap. 26). Accelerating global warming since the 1980s has raised the possibility of more abrupt or extreme climatic change, beyond the adaptive capacity of the current food system. On the one hand, it seems unlikely that climate change will so reduce food production as to threaten global food shortages in the next few decades. Food supplies have risen faster than population since the early twentieth century. The considerable share of global food production either wasted or devoted to beef production should leave significant spare capacity for human food supplies - eBook - ePub

Dust Bowl

Depression America to World War Two Australia

- Janette-Susan Bailey(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

91Hogue’s Drouth Stricken Area shows an abandoned farm engulfed by endless waves of drift sand (Fig. 4.2 ). All signs of civilization are broken or lie buried under desert sands. A windmill, now useless, stands broken. By the windmill, a bull so important to civilization, has been left behind and starving, now searches for water in a tank filled with sand. A vulture waits—he will be the only one left soon. Dust Bowl (1933) also featured (see newspaper image, Fig. 4.7 ). Dust Bowl shows destructive tractor tire tracks and fence-lines in the foreground, a homestead in the background of a desert expanse. The whole image in its brilliant orange and red tones is framed by an oppressive heat and a sense of loss the viewer can feel.A scorching sunset on the horizon frames this waterless place with a heavy sense of oppressive heat. Hogue provided no desert gardens. There are no happy endings in his painting, nor in his commentary on the pumping of water from the region’s great aquifer. Instead, he warned:the Ogallala aquifer is the largest in the world. But since millions of acres of wheat are irrigated from it, it will soon be dry for several thousand years leaving Llano Estacado a desert.92Women and Human Erosion: Ma Joad, Woman of the High Plains , and Migrant Mother

The idea of a permanent desert decline is also clear in gendered Dust Bowl narratives. They reflect that traditional and paradoxical set of beliefs about deserts, women, progress, and civilization—and the connections in between. Here, the idea of “the family as the traditional unit of our civilization,” was expressed in the image of the housewife and mother.93Conventional images showed her as orderly, slim but healthy, fashionable and attractive, clean and tidy, and almost always operating in and closely around the domestic sphere. However, human erosion narratives took her away from the homestead and into the wilderness. To dramatize the idea of a soil/human interrelationship, they drew on the Judeo–Christian idea of “desert” as a “deserted place or wilderness.”94Photographers such as Dorothea Lange expressed this by capturing images of depression-era poverty, but Lange remained wary of Stryker’s ideas, conceived of in Washington, DC, so far away from the influence of her subjects in the West. Featuring in Lange and Taylor’s An American Exodus, Woman of the High Plains (1938) is one of those images but the subject is not a refugee. In this image, the “wilderness” of the Dust Bowl is the place into which she has been cast. Impoverished by it, she struggles to survive in the Texas Panhandle. The caption, quoted from the subject, Nettie Featherston reads, “when you die you’re dead, that’s all.”95Unlike Woman of the High Plains, in many of Lange’s photographs, women are often no longer in the Dust Bowl and have become refugees. On the road or in migrant camps, they symbolize civilization, once the pioneering conqueror of deserts and wastelands, expelled by the very desert it has created.96 - eBook - ePub

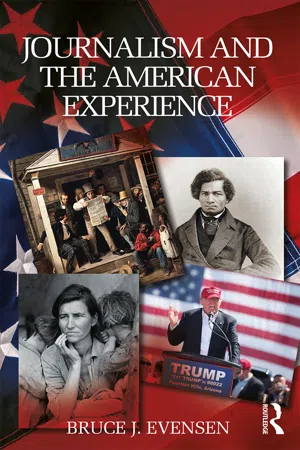

- Bruce J. Evensen(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Ochiltree County Herald reported Texas had “nothing like it on record.”Associated Press reporter Robert Geiger, overtaken by the storm outside Boise City, Oklahoma, wrote of the “Dust Bowl” in describing Black Sunday. The term seemed to capture the pitiful plight of the Plains. Bennett seized on this moment to implore lawmakers to do something “to avoid calamity in the rural West.” The Washington Post reported that government office workers “swarmed down the Mall and to Potomac Park” to watch the dust show, when it reached the nation’s capital. On April 23 House and Senate conferees approved a plan to permanently fund a Soil Conservation Service. Four days later President Roosevelt signed the measure. Bennett’s soil conservation practices eventually reversed the dust storms, but for many it came too late. Half of a million had been made homeless during the decade of the Dust Bowl. Two and a half million others fled the Southern Plains. They would be among those loosened from the land that photographers would gaze at in some bewilderment in Nipomo pea patches. Their tragedy was only part of the sad spectacle of the interwar era.A speculative splurge during the prosperity decade of the 20s boosted the market’s value seven times over, making many millionaires. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover campaigned for president in the summer and fall of 1928 based on a continuation of policies that in his view had led to that prosperity. In 1921, Warren Harding had put it simply before a joint session of Congress: “We want less of government in business as well as more business in government.” Harding’s successor Calvin Coolidge stated in his 1928 State of the Union Address that the nation had never known “a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time.” Hoover observed, “We in America today are nearer the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any other land. The poorhouse is vanishing from among us.” His successful campaign promised “a chicken in every pot and a car in every backyard.” A vote for Hoover was “a vote for prosperity.” Even Democratic National Committee Chairman John K. Raskob seemed to agree with Hoover, telling an interviewer from Ladies Home Journal - eBook - PDF

- Marnie M. Sullivan, John Olszowka, Brian R. Sheridan, Dennis Hickey(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Syracuse University Press(Publisher)

It is clear from his dispatches that farmers and readers alike were aware that unsuitable farming practices and pasture overuse had played key roles in damaging the plains and prolonging the Dust Bowl; however, Pyle is careful not to assign blame. Metaphors subtly rein- force the central role of humans in ruining the land. He refers to sickening “pillars of sand—giant columns, miles away, rising from the horizon clear up to the sky, like smoke from a burning town.” Pyle mentions the scientists and government officials responding to the crisis, alluding to the tension between progress, farmers, and the exploitation of the land. When reflecting on the painful question of what might happen to the Great Plains region, he acknowledges that the “experts are working on it. They are giving advice, but advice is mighty hard to follow when you’re broke.” Pyle helped Depres- sion Era readers across the nation strengthen their own resolve with such accounts of life in the Dust Bowl. Photographers, filmmakers, and other visual artists joined journalists in covering the Dust Bowl. Dorothea Lange made a name for herself docu- menting life during the Dust Bowl as a photographer with the Farm Secu- rity Administration. Driven, hardworking, and talented, Lange traveled with migrants and the images she captured portray the utter destitution of dispir- ited families. Photographs like Lange’s iconic “Migrant Mother” brought the face of suffering to a sympathetic American public. Federal monies funded the filmmaker Pare Lorentz’s significant documentary The Plow That Broke the Plains. Like Lange, Lorentz was driven and talented. He was also idealistic and motivated by a powerful conviction that film could provide 56 a m e r i c a i n t h e t h i r t i e s more than distraction for audiences. He wanted to make substantial films of merit that might inspire answers to the problems faced by Americans during the Great Depression.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.