Psychology

Health and Happiness

Health and happiness are interconnected aspects of well-being that encompass physical, mental, and emotional states. Health refers to the overall condition of the body and mind, while happiness involves experiencing positive emotions and life satisfaction. Research in psychology explores the relationship between health and happiness, highlighting the impact of psychological factors on physical health and the role of positive emotions in promoting well-being.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

12 Key excerpts on "Health and Happiness"

- eBook - ePub

Well-Being in Adolescent Girls

From Theory to Interventions

- Elena Savina, Jennifer M. Moran(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1 Well-Being Definitions and FrameworksDOI: 10.4324/9781003105534-1In 1948, the World Health Organization defined health as a “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1948 , p. 28). This definition provided a vision for the mental health field delineating positive aspects of human functioning. Nevertheless, for many years a medical model dominated the field. This model defined health as the absence of illness, rather than the presence of wellness. This medical model “narrows our focus on what is weak and defective about people to the exclusion of what is strong and healthy. It emphasizes abnormality over normality, poor adjustment over healthy adjustment and sickness over health” (Maddux, 2008 , p. 56). Furthermore, the medical model places adjustment and maladjustment inside the person, but disregards complex person-environment interactions, social and cultural values, and the role of societal institutions in human functioning.In the 1990s, the positive psychology movement shifted the focus away from pathology and toward human strength, resiliency, and positive functioning. One of the founders of positive psychology, Martin Seligman, argued that:psychology is not just the study of disease, weakness, and damage; it is also the study of strength and virtue. Treatment is not just fixing what is wrong; it is also building what is right. Psychology is not just about illness or health; it also is about work, education, insight, love, growth, and play.(Seligman, 2002 , p. 4)Positive psychology became the study of the strengths and virtues that allow both individuals and communities to thrive (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ). Seligman (2002 ) further proposed a concept of positive mental health that delineated human flourishing and living a fulfilled life. This concept places human functioning on a continuum, with mental illness representing one end of the continuum and optimal psychological health the other. Human well-being became a central concept in positive psychology (Seligman, 2011 - eBook - ePub

- Anthony Curtis(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1 Introduction to Health Psychology Defining health psychology Historical perspective on health and illness The biomedical model The biopsychosocial model Psychology and health Models of behaviour change SummaryWelcome to the fascinating area of health psychology! This text aims to provide an insight into the many fields that make up health psychology. You may be a student, nurse or other practitioner in the health field, or just seeking to find out more about your health and the role that psychology can play in understanding health states and health status. I hope that this book is of interest to you and relevant to your needs.Defining Health PsychologyIn trying to define health psychology, one must first try and define what is meant by ‘health’ as a concept. The most commonly quoted definition of health is provided in the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO, 1946):Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.This definition is considered to have positive and negative attributes by Downie et al. (1996). In the first part of the definition, they argue that health is seen in positive terms (i.e. the presence of a positive quality: well-being). In the second part of the definition, health is viewed (in a negative sense) as involving the absence of disease or infirmity (themselves negative in connotation). Taken together, the definition implies that true health involves both a prevention of ill-health (e.g. disease, injury, illness) and the promotion of positive health, the latter of which has been largely neglected.Banyard (1996) has criticised the above definition on the grounds that a state of complete - eBook - ePub

Sustainable Development

Capabilities, Needs, and Well-being

- Felix Rauschmayer, Ines Omann, Johannes Frühmann, Felix Rauschmayer, Ines Omann, Johannes Frühmann(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2 From a psychologist’s perspective, we introduce a second framework that has been developed in research on human flourishing and mental health. This approach also goes beyond happiness and takes into account the individual’s self-realization as well as social integration and contribution in defining a good life. The challenge here will be to integrate this psychological perspective with the capabilities and sustainable development approaches.It must be noted that the concepts of happiness, quality of life and well-being used in this chapter are somewhat different from those proposed in the first chapter of this book (Rauschmayer et al.). Happiness is considered a more or less temporary and subjective sensation of feeling well. In the psychological literature, happiness has also been described as subjective, emotional or hedonic well-being. In economic terms, quality of life indicates the extent to which needs are met enabling human flourishing in its fullest sense. From a psychological point of view human flourishing consists of the fulfilment of individual strivings towards self-realization and social integration. The subjective evaluation of the fulfilment of these two needs is designated as psychological well-being and social well-being respectively. Together, these two forms of well-being constitute what has been called eudaimonic well-being. Hence, well-being consists of happiness and quality of life from an economic perspective, whereas it is made up of happiness, psychological, and social well-being from a psychological perspective.1In the second section of this chapter the classical economic and psychological theories based on consumption and/or individual preferences are criticized. In both scientific branches new tendencies claim that other indicators must be added or found. The third section presents the example of the capability approach of Sen, some theories on needs and the eudaimonic approach in psychology that were also developed in the first chapter of this book (Rauschmayer et al - eBook - ePub

Thinking about the Lifecourse

A Psychosocial Introduction

- Elizabeth Frost, Stuart McClean(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

In this chapter, then, we consider how we can link up some of these ideas and consider how well-being can be psychosocially conceptualized. We start by looking at health and well-being briefly, then draw on some classic philosophy to orientate our ideas. We spend some time discussing the strengths and problems with key ideas from positive psychology before exploring some nuanced notions of, for example, ‘good enough’ well-being from object relations theorists. A critique of self-help and self-oriented ‘methods’ for fulfilment is offered by highlighting Giddens’ work. A central section of the chapter considers the psychosocial notions of resilience and of relational well-being and friendship, though Honneth’s work on recognition mainly falls in the next chapter in relation to ‘ill-being’. At the end we look briefly at how individuals frequently describe their own well-being as connected to life-changing events. Primarily, then, this chapter considers how best we can understand well-being within a psychosocial framework and as such some cross-referencing with ‘ill-being’ in the next chapter will be used here; this chapter and the next should therefore be read together.Health and well-being

‘Well-being is a quality in demand in today’s society’ suggests Sointu (2005: 255), and feelings of well-being are ‘regarded as a state of virtue’ (Furedi, 2003: 31). We may consider why this is. Some of the questions we could ask ourselves and have been asked by others are, is well-being about happiness, is it about success or achievement, or is it in a psychosocial sense about how you are doing well in the world? In the broader context of the individual and their growth and development, is it also about equality and ‘the good society’?Over a half a century ago, in 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) at the World Health Assembly came up with their definition of health that broadened the concept of health to include, as they saw it, the psychosocial dimension, taking into account subjective experience: ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (World Health Assembly, 1948). This is one of their most well-known and oft-cited statements, and the term ‘psychosocial well-being’ has since become popular in the study of mental health, for example, adopting the WHO definition. - eBook - ePub

Adaptation and Well-Being

Meeting the Challenges of Life

- Knud Larsen(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Since happiness is related to health, what can society do to increase happiness? An important factor that impacts happiness scores is improving the liveability of society by creating better macro-social conditions. In one study, happiness scores varied from the lowest scores, found in Tanzania, to the highest happiness scores in Denmark. People are happier in materially richer countries that practice democracy and freedom of choice. Happiness and therefore health can be promoted by policies that aim at establishing decent standards of living in societies where people don’t experience the threat of oppression and where the voice of ordinary people matters (Veenhoven, 2005, 2008; Zautra, 2003).Other reviews suggest that optimistic emotions, even when unrealistic, have positive consequences affecting the onset of physical illness. Although the pathways are not clearly understood, it appears that positive emotions have some physical protection benefits, perhaps through strengthening the immune system. Positive people may also develop better coping strategies. A psychologically positive outlook on life acts as a stress buffer so that the happy individual is less likely to develop the many chronic illnesses associated with the stress of living in modern competitive societies. Society would be well served by promoting social well-being policies given the high costs of illness and early deaths. Well-being is not just an individual goal, but in order to be achieved, must include economic and political objectives as well. Health from the perspective of positive psychology must, of necessity, be multidisciplinary, taking into account the individual, but also social, institutional and political spheres (Vazquez, Herves, Rahona & Gomez, 2009).Happiness is a deep personality trait that helps the individual cope well with adversity. Life is difficult for all humans, and for some people, it is very hard with the tragic impact of disease and early death. Since it is not possible to divorce ourselves from tragedy, happiness must have something to do with how people handle adverse events and the hardiness of personalities. People develop varying ways of coping with stressful life events that either undermines or is beneficial to health. The autonomic nervous system is engaged whenever stress is experienced and people develop lifelong coping patterns that either elevate or control these responses that, in turn, affect health outcomes. In one longitudinal study done with Catholic nuns, researchers found a very strong association between positive emotional content of autobiographies and longevity 60 years later. These findings are consistent with other studies that show that optimism is associated with longevity. Of course, optimistic people also face tragedy in life, but they have the ability to accept it and regroup with hope for the future. Future research may illuminate the underlying physiological and brain processes that are associated with happiness (Danner, Snowdon & Friesen, 2001). - eBook - ePub

- Marie Louise Caltabiano, Lina Ricciardelli(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

In 1946 the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a revised definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1946, p. 100). However, the traditional “disease model” of human functioning, which focused primarily on pathology, weaknesses, and treating illness, persisted. By including psychological and social aspects of individual health, concerns regarding wellbeing and satisfaction with life began to emerge.Martin Seligman (2002, 2003) proposed a paradigm shift to a positive model of psychology, which focused on positive subjective experiences, strengths, and promoting health and wellbeing. Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) predicted that positive psychology would “allow psychologists to understand and build those factors that allow individuals, communities, and societies to flourish” (p. 13). Positive psychology, as a theoretical framework, does not imply the dichotomization of human experience into positive or negative; rather it views experience as a continuum that spans the whole spectrum of human experiences from health to illness and from distress to wellbeing (Keyes, 2002; WHO, 2005). For example, positive and negative psychological states can occur contiguously or even simultaneously, and even when faced with highly stressful circumstances, positive psychological states can occur (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000).Gable and Haidt (2005) defined positive psychology as “the study of the conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing or optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions” (p. 104). Seligman (2003) forwarded three pillars of positive psychology: positive subjective experiences (e.g., optimism, hope, happiness); positive individual characteristics (e.g., personal strengths that promote mental health); and positive social institutions and communities (e.g., those that contribute to individual happiness and health). According to Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000), “the aim of Positive Psychology is to begin to catalyse a change in the focus of psychology from a preoccupation only with repairing the worst things in life to also building positive qualities” (p. 5). - eBook - ePub

Everyday Applications of Psychological Science

Hacks to Happiness and Health

- R. Eric Landrum, Regan A. R. Gurung, Susan A. Nolan, Maureen A. McCarthy, Dana S. Dunn(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Section 5 In closingMy happinessDOI: 10.4324/9781003188711-6In some ways, everything in this book – all of the preceding sections – were related to happiness, overall life satisfaction, or what psychological scientists might precisely label as “subject well-being.” As you might imagine, there is quite a bit of research and scholarship available about happiness, and many of the relationships between happiness and health and wealth have been presented in previous sections. What are the benefits of happiness? Happier people live longer, experience fewer illnesses, remain married longer, are more creative, earn more money, are more helpful to others, and tend to work harder and better in their professions.Two main takeaways that prominent happiness researchers1 would want us to know are that (1) happiness is a process, not a place, and (2) happiness more than feels good; it is good for you (i.e., it is to be used and enjoyed).Part 5.1 Subjective well-being and why it matters

For most people, happiness is a present state of being, one based in emotion, as in “I am happy” or “I feel pretty happy.” Good feelings are associated with a moment in time – how individuals feel about their world and their place in it. This approach makes sense because when a peer asks us, “How are you doing?”, we reflect on how we feel right then and there. We are less likely to think about how happy we are in the big picture of our lives, which might require more reflection and a more detailed answer than our friend’s polite inquiry was actually after.In contrast, psychologists are usually interested in a broader view of people’s happiness, and they often refer to measuring people’s subjective well-being. “Subjective” is the key word because it implies that self-reports about people’s states are personal, slanted by their experience and perspective, and open to very little independent verification. I know how I feel but I can only guess how a friend or a stranger is feeling. Subjective well-being and the variety of psychological measures used to assess it point to what are known as individual differences in psychology, that is, people’s responses to them vary. For our purposes, some people report higher subjective well-being than others, though most people do report being relatively happy.2, 3, 4 Indeed, people may report being above the neutral point of happiness but they may not be satisfied with their lives, that is, their personal and societal situations.5 To be very happy, you need both very desirable personal circumstances and to live in an affluent, contented culture with close, reliable ties with other people.6 - Robbert Sanderman, Dominika Kwasnicka, Robbert Sanderman, Dominika Kwasnicka(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

First, you will notice that some of the health models use the term well-being to characterize an individual’s overall state of health. As noted in Chapter 1, An Interdisciplinary View of Health, well-being describes the state of the body (physical), the mind (psychological), the spirit, and social relations (emotions). It offers a holistic view of health similar to the ecological model, with one distinction. The ecological model does not specifically address spiritual health. It does, however, include physical environmental factors as well as health systems and health policy determinants. Because well-being incorporates many of the same determinants found in the biopsychosocial model, we will use this term rather than health to characterize a person’s overall condition (physical, psychological, emotional, and social). When applicable, we will add to this concept the effects of the physical and psychological environment, health systems, and health policy on health outcomes to explain the ecological model. Second, and equally as important, by using the term well-being we are reminded that a thorough study of health integrates the emotional and psychological states of an individual. It further supports the inclusion of health psychologists into the practice of and research on health. SECTION I. FOUR MODELS OF WELL-BEING Biomedical Model The first formal, Western model of well-being, here meaning a model supported by scientific inquiry and empirical study, is the biomedical model. In favor since the early 20th century, the biomedical model proposed that health is the absence of disease or dysfunction. Using this definition as a starting point, disease was defined as an abnormality, specifically a dysfunction of or deviation in a body organ or other body structure (Engel, 2002; Wade & Halligan, 2004)- eBook - ePub

Redefining Well-Being in Nations and Organizations

A Process of Improvement

- Ali Qassim Jawad, William Scott-Jackson(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

One of the confusing aspects of well-being in research and practice is that the concept is ill-defined or rather is well-defined but defined very differently in various disciplines. The definitions tend to range from notions of overall health (physical or psychological – often separated) to an assumed state of sustained contentment caused by a range of input factors such as housing, employment, health, social life and so on. It is conflated with related constructs such as quality of life, happiness, health and engagement. In organizational settings and literature, it is most commonly differentiated from ‘engagement’, with ‘well-being’ representing mental and physical health (Utriainen et al. 2014), and ‘engagement’ representing work-focused energy leading to higher productivity at work (Costa et al. 2014). One of the issues is that the conception of well-being can be seen as a philosophical question to do with the observer’s viewpoint (Varelius 2004), including whether well-being is an objective quality of life (that is factual and non-perceptual) or whether it is a response to situations, as perceived and experienced differently by different individuals (that is subjective response to stimuli).Well-being is most often defined as a worthwhile outcome in its own right (in contrast with engagement, for example, which most often seen as a way of achieving valued outcomes such as productivity). However, some researchers have investigated the results of well-being, including Bryson et al. (2014), who found clear associations between well-being and workplace performance and quality but no association between short-term positive/negative work-related affect and performance.Many definitions of well-being include assumptions on its causes or components. Michaelson et al. (2012: 6), for example, in pointing out the difference between short-term happiness and longer-term well-being, state that well-being includes ‘happiness but also other things such as how satisfied people are with their lives as a whole and things such as autonomy (having a sense of control over your life) and purpose - eBook - ePub

ExecutiveHealth.com's Leading Under Pressure

Strategies to Avoid Burnout, Increase Energy, and Improve Your Well-being

- Gabriela Cora(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Career Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 3THE HEALTHY INDIVIDUALThe World Health Organization defines health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. All effective interventions in medical psychiatry include the bio-psycho-social approach. As healthcare dollars have continued to shift toward expert and expensive procedures, preventive approaches to health and wellbeing have become segmented and limited. It is not uncommon for a busy executive or professional to have a physical evaluation by his or her internist, receive medication therapy from a psychiatrist, receive psychotherapy from a therapist, and receive coaching from someone else. This disintegrated approach forces the busy businessman or woman to remember what was said to whom, where, and when. Making everyone talk while in separate systems is one of the most significant challenges when providing care. The paradox lies in how to enhance a holistic approach while addressing specific needs at the same time.If we consider our self as a system in full operation with structures (dimensions) and interactive processes (performance and productivity) working in full alignment and in unison, we will find the much desired system in balance. To optimize this process, we need to know the exact characteristics of the structure, its potential, and its deficiencies. If there is a problem in one area, the problem needs to be fixed in that same area. If one area or dimension is severely impaired or affected for an extended period of time, other dimensions will most likely be affected as well. The more severely impaired and the longer the impairment, the more structures and processes that may need to be repaired across dimensions.An individual self has several systems or dimensions in operation, including the physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual. We can maximize our performance and productivity as active processes within each and every dimension. By better understanding each dimension we can improve and maximize our performance and productivity within each as we integrate our efforts in balancing our system. - eBook - ePub

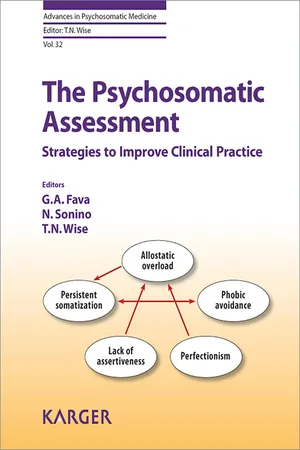

- G. A. Fava, N. Sonino, T. N. Wise(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- S. Karger(Publisher)

130 ].Conclusions

Recent literature [28 , 138 , 139 , 158 ] suggests that positive affect and well-being represent protective factors for health. Their presence could reduce the activation of neu-roendocrine, autonomic and cardiovascular systems through the deactivation of the limbic prefrontal circuits responsible for the reactions to stressful events [159 ]. The results of the previous studies confirm the hypothesis that well-being and ill-being are two separate but related concepts [27 , 28 , 138 , 139 ]. They both contribute to influence health, as confirmed by different biological parameters which are involved. In the psychosomatic setting, where the biopsychosocial model of health has been proposed long time ago, the assessment of psychological well-being together with the assessment of distress thus becomes crucial and could be easily performed using instruments such as the SQ, the SOC, the Psychological Well-Being Scales and the I Psychosocial Index, provided in the online supplementary appendix. These tools examine different aspects of positive functioning (i.e. positive affectivity, salutogenesis, positive psychological well-being), providing different sets of information which are all important in defining a patient's complete health status. These instruments could also highlight specific impairments in well-being, which constitute vulnerability factors for health and influence other issues such as motivation, compliance to treatment and health risk behaviors. The identification of these impairments in well-being could then be addressed by psychosocial interventions aimed at increasing positive functioning such as well-being therapy [153 ]. An increase in psychological well-being may counteract the feelings of demoralization and loss which are part of chronic disease and thus improve the individual coping. Disorders related to somatization - defined as the tendency to experience and communicate psychological distress in the form of physical symptoms and to seek medical help for them [9 ] - may also derive some benefit from well-being-enhancing strategies. It is thus conceivable that well-being therapy or other similar positive interventions [160 ] may yield clinical benefits in improving QoL, coping style and social support in chronic and life-threatening illnesses, as was shown for cognitive behavioral strategies [161 - eBook - ePub

- Kathleen Galvin, Kathleen T. Galvin(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

happiness as equilibrium.It follows from this characterization that happiness must be a dimensional concept. P can be more or less happy with life according to the degree of agreement between the state of the world as P sees it, and P’s wants. Moreover P can be completely happy with life only if his conditions in life are exactly as he wants them to be. Similarly, P is completely unhappy with life, only if nothing in P’s life is at all as P wants it to be. There is then a continuum from complete happiness to complete unhappiness. This continuum of happiness must be distinguished from any particular state of happiness.3A question

Now, is this understanding of quality of life universal in the discussion about quality of life in health care? We can hardly say that. Although there has been a tendency in the subjectivist direction it is far from clear in most instances how this subjectivism should be interpreted. One reason behind this obscurity is the lack of a thorough theoretical discussion about happiness and quality of life in health care. Please don’t misunderstand me. There is not a lack of theoretical analysis of these concepts within philosophy or sociology. The lack is noticeable within the health sciences. Most constructors of instruments for the measurement of quality of life in health care do not take the time or do not make the effort to analyze the basic concepts. They have preferred different routes, mainly relying on questionnaires and interviews with a sample of people. Another source of confusion is that some instrument constructors prefer the term, and perhaps also the notion, “health” to the notion quality of life. It is thus unclear whether the constructor measures health or quality of life. I will return to this issue and discuss it more thoroughly below.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.